Showing 1–16 of 166 resultsSorted by latest

-

Issue #166

Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry

$8.99 – $18.00Price range: $8.99 through $18.00

The Winter 2025-26 issue features poetry and prose by Alice Hoffman, Victoria Chang, Reginald McKnight, Maggie Dietz, Amy Gerstler, Jennifer Martelli, and Michael Burkard. Cover art by Mary Royall Wilgis.

-

Issue #165

Fiction

$8.99 – $18.00Price range: $8.99 through $18.00

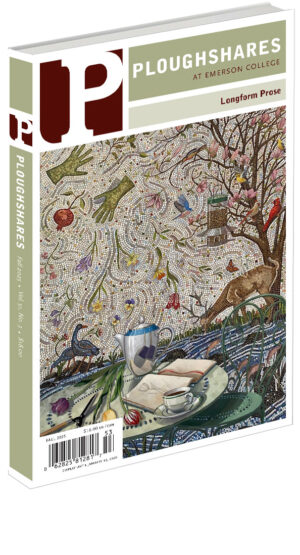

The Fall 2025 issue features longform prose by Devon Walker-Figueroa, Geetanjali Shree (translated by Daisy Rockwell), and more. Cover art by Barbara Kassel.

-

Issue #164

Fiction

$8.99 – $18.00Price range: $8.99 through $18.00

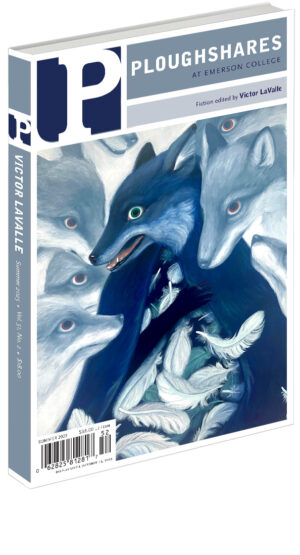

The Summer 2025 issue, guest edited by Victor LaValle, features prose by Helen Phillips, Deesha Philyaw, S. A. Cosby, Joanna Pearson, Carolyn Ferrell, and more, as well as an interview with the Ashley Leigh Bourne Prize for Fiction winner, Ramona Ausubel. Cover art by Laura Catherwood.

-

Issue #163

Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry

$8.99 – $18.00Price range: $8.99 through $18.00

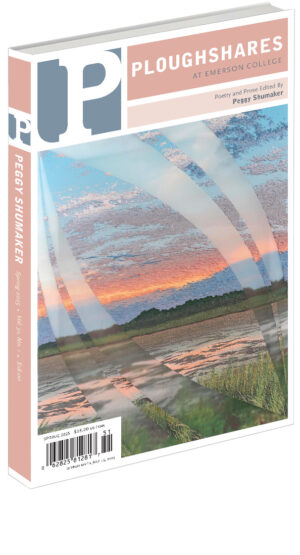

The Spring 2025 issue, guest edited by Peggy Shumaker, features poetry and prose by Naomi Shihab Nye, Felicia Zamora, Tim Seibles, Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, Lia Purpura, Sonja Livingston, Marjorie Sandor, and more, as well as an interview with the Alice Hoffman Prize for Fiction winner, Jen Silverman. Cover art by Saskia Fleishman.

-

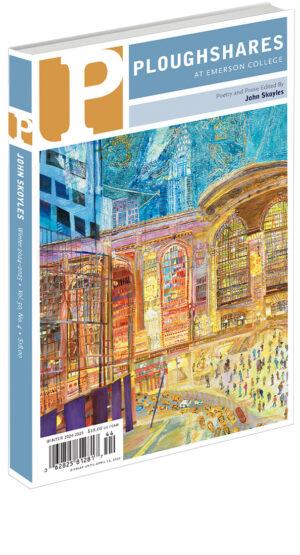

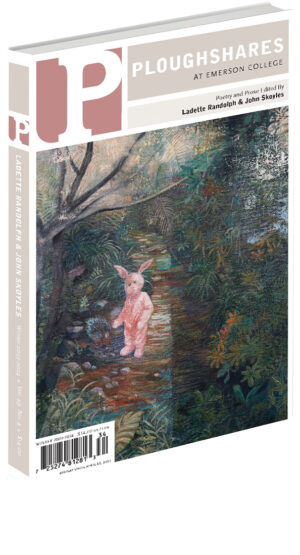

Issue #162

Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry

$8.99 – $18.00Price range: $8.99 through $18.00

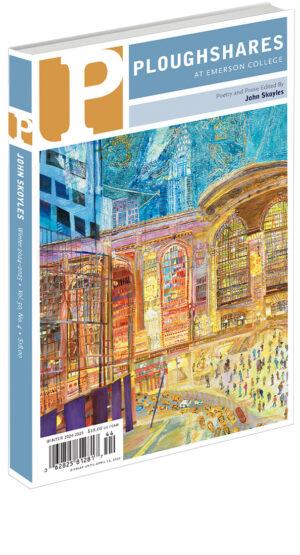

The Winter 2024-25 issue, guest edited by John Skoyles, features poetry and prose by Joan Silber, Timothy Liu, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Emily Fragos, Charles Baxter, Rasaq Malik Gbolahan, Malena Mörling, and more, along with work by the Emerging Writer’s Contest winners Susan Bartolme, Andy Chen, and Billy Lezra, and an interview with the John C….

-

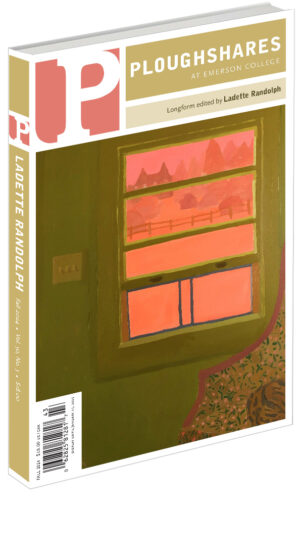

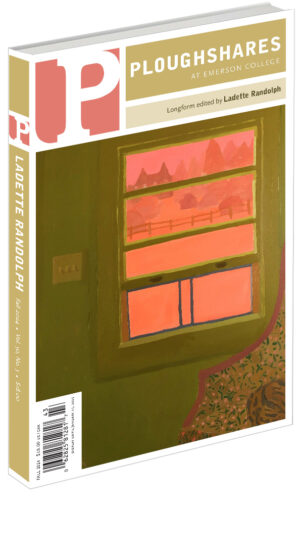

Issue #161

Longform

$8.99 – $18.00Price range: $8.99 through $18.00

The Fall 2024 issue features longform prose by Andre Dubus III, Gretchen Ernster Henderson, Benjamin Hoffmann, Aiysha Jahan, Joy Notoma, Shuchi Saraswat, Jen Silverman, Richard Stock, and Daniel Taylor. Cover art by Sophie Treppendahl.

-

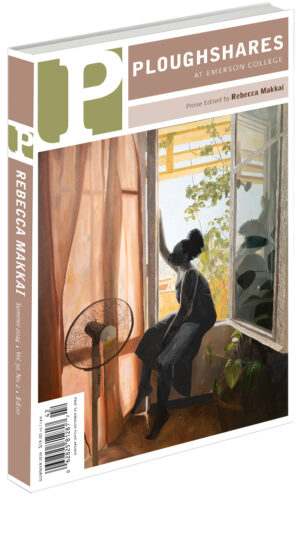

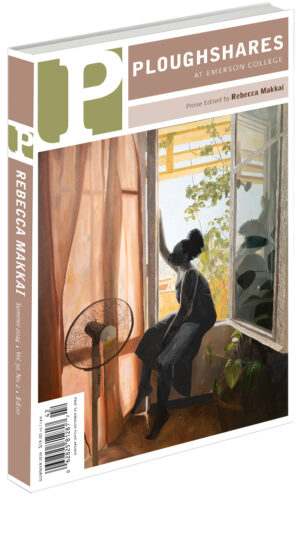

Issue #160

Fiction, Nonfiction

$8.99 – $18.00Price range: $8.99 through $18.00

The Summer 2024 issue, guest-edited by Rebecca Makkai, features prose by Dur e Aziz Amna, Ramona Ausubel, Peter Mountford, Khaddafina Mbabazi, DK Nnuro, and more, as well as an interview with the Ashley Leigh Bourne Prize for Fiction winner, Andre Dubus III. Cover art by Elladj Lincy Deloumeaux.

-

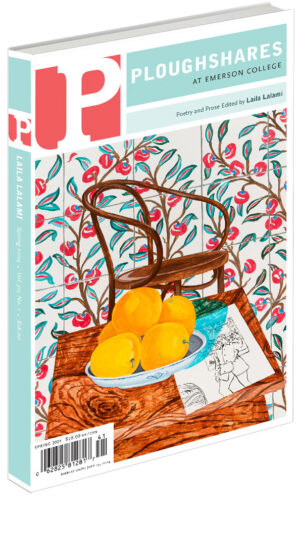

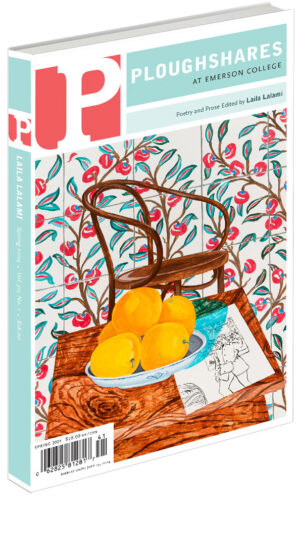

Issue #159

Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry

$8.99 – $18.00Price range: $8.99 through $18.00

The Spring 2024 issue, guest-edited by Laila Lalami, features poetry and prose by Mosab Abu Toha, Nathalie Handal, January Gill O’Neil, Farah Abdessamad, Francisco Goldman, Tommy Orange, and more, as well as an interview with the Alice Hoffman Prize for Fiction winner, Molly Aitken. Cover art by Sierra Montoya Barela.

-

Issue #158

Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry

$6.99 – $14.00Price range: $6.99 through $14.00

The Winter 2023-24 issue, features poetry and prose by Richard Bausch, Jesse Lee Kercheval, Ian Stansel, Ariana Benson, Rebecca Morgan Frank, Marie Howe, and more, along with work by the Emerging Writer’s Contest winners Logan Klutse, J Lazar, Mengyin Lin, and an interview with the John C. Zacharis First Book Award winner, Claire Luchette. Cover…

-

Issue #157

Longform

$6.99 – $14.00Price range: $6.99 through $14.00

The Fall 2023 issue features longform prose by Anthony David, Parul Kapur, John Keeble, Diane Hinton Perry, Austin Woerner, Nafis Shafizadeh, Wiam El-Tamami, Jamie Lyn Smith, and Jim Shepard. Cover art by Arghavan Khosravi.

-

Issue #156

Fiction, Nonfiction

$6.99 – $14.00Price range: $6.99 through $14.00

The Summer 2023 issue, guest edited by Tom Perrotta, features prose by Marianne Leone, Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, Andre Dubus III, and more, as well as an interview with the Ashley Leigh Bourne Prize for Fiction winner, E.K. Ota. Cover art by Byron Kim.

-

Issue #155

Fiction, Nonfiction, Poetry

$6.99 – $14.00Price range: $6.99 through $14.00

The Spring 2023 issue, guest edited by Alice Hoffman, features poetry and prose by Danusha Lameris, Jennifer Haigh, Victor LaValle, and more, as well as an interview with the Alice Hoffman Prize for Fiction winner Kashona Notah. Cover art by Helen Zughaib.

-

Issue #154

Fiction

$6.99 – $14.00Price range: $6.99 through $14.00

The Winter 2022-23 issue features poetry and prose by Alice Jolly, Natalie Bakopoulos, Carmen Giménez, and more, along with work by the Emerging Writer’s Contest winners Catherine Kim, Giovannai Rosa, and Megan Valley, and an interview with the John C. Zacharis First Book Award winner Lara Egger. Cover art by Tiffanie Delune.

-

Issue #153

Longform

$6.99 – $14.00Price range: $6.99 through $14.00

The Fall 2022 issue features longform prose by E. K. Ota, Ben Stroud, and more. Cover art by David Thuku.

-

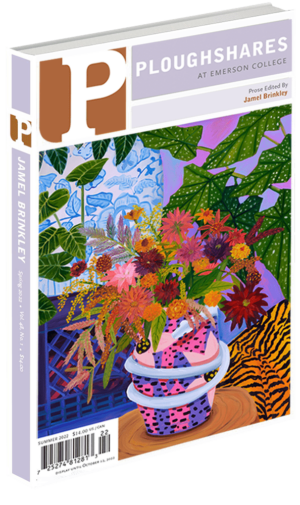

Issue #152

Fiction, Nonfiction

$6.99 – $14.00Price range: $6.99 through $14.00

The Summer 2022 issue, guest edited by Jamel Brinkley, features prose by Rav Grewal-Kök, Arinze Ifeakandu, and more, as well as an interview with the Ashley Leigh Bourne Prize for Fiction winner, Christie Hodgen. Cover art by Anna Valdez.

-

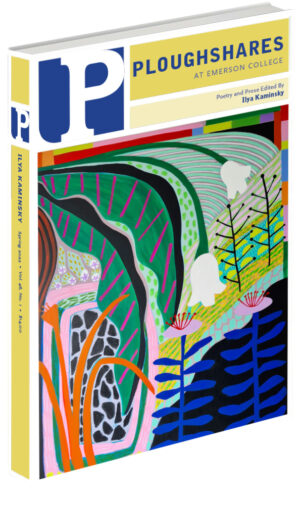

Issue #151

Fiction, Poetry

$6.99 – $14.00Price range: $6.99 through $14.00

The Spring 2022 issue, guest edited by Ilya Kaminsky, features poetry and prose by Sheila Black, Andres Cerpa, and more, as well as an interview with the Alice Hoffman Prize for Fiction winner Fei Sun. Cover art by Amy Kim.