Summer 2025

$8.99 – $18.00The Summer 2025 issue, edited by Victor LaValle, features prose by Helen Phillips, Deesha Philyaw, S.A. Cosby, Joanna Pearson, Carolyn Ferrell, and more. Cover art by Laura Catherwood.

Ploughshares publishes issues four times a year. Two of these issues are guest-edited by different, prominent authors. The other two issues are edited by our staff editors, one a mix of poetry and prose and the other long-form prose.

Showing 1–16 of 164 resultsSorted by latest

The Summer 2025 issue, edited by Victor LaValle, features prose by Helen Phillips, Deesha Philyaw, S.A. Cosby, Joanna Pearson, Carolyn Ferrell, and more. Cover art by Laura Catherwood.

The Spring 2025 issue, guest edited by Peggy Shumaker, features poetry and prose by Naomi Shihab Nye, Felicia Zamora, Tim Seibles, Lena Khalaf Tuffaha, Lia Purpura, Sonja Livingston, Marjorie Sandor, and more. Cover art by Saskia Fleishman.

The Winter 2024-25 issue, guest edited by John Skoyles, features poetry and prose by Joan Silber, Timothy Liu, Pádraig Ó Tuama, Emily Fragos, Charles Baxter, Rasaq Malik Gbolahan, Malena Mörling, and more.

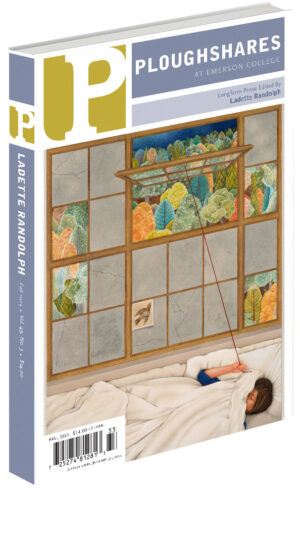

The Fall 2024 Issue, edited by Ladette Randolph, features prose by Andre Dubus III, Gretchen Ernster Henderson, Benjamin Hoffmann, Aiysha Jahan, Joy Notoma, Shuchi Saraswat, Jen Silverman, Richard Stock, and Daniel Taylor.

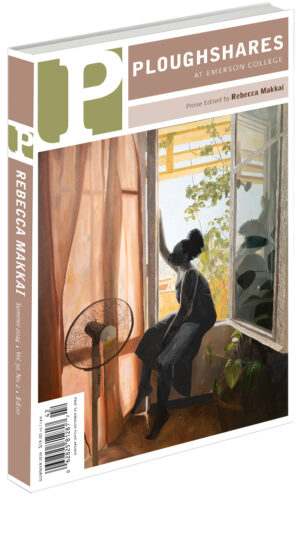

The Summer 2024 Issue, guest-edited by Rebecca Makkai, features prose by Dur e Aziz Amna, Ramona Ausubel, Peter Mountford, Khaddafina Mbabazi, DK Nnuro, and more.

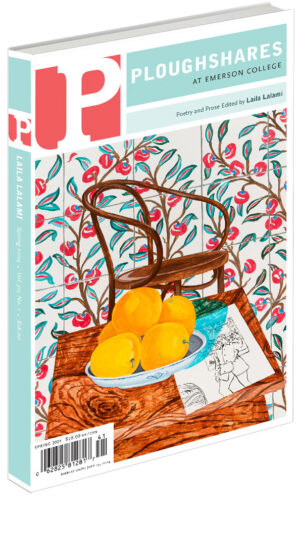

The Spring 2024 Issue, guest-edited by Laila Lalami, features poetry and prose by Mosab Abu Toha, Nathalie Handal, January Gill O’Neil, Farah Abdessamad, Francisco Goldman, Tommy Orange, and more.

The Winter 2023-24 Issue, edited by Ladette Randolph, features poetry and prose by Richard Bausch, Jesse Lee Kercheval, Ian Stansel, Ariana Benson, Rebecca Morgan Frank, Marie Howe, and more.

The Fall 2023 Issue, edited by Ladette Randolph, features prose by Anthony David, Parul Kapur, John Keeble, Diane Hinton Perry, Austin Woerner, Nafis Shafizadeh, Wiam El-Tamami, Jamie Lyn Smith, and Jim Shepard.

The Summer 2023 Issue, guest-edited by Tom Perrotta, features prose by Marianne Leone, Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan, Andre Dubus III, Fabio Morábito, Jen Trynin, Olufunke Grace Bankole, and Jess Walter, among others.

The Spring 2023 Issue, guest-edited by Alice Hoffman, features poetry and prose by Danusha Lameris, Jennifer Haigh, Victor LaValle, Mary Gordon, Diane Ackerman, Lavanya Vasudevan, and Jai Chakrabarti, among others.

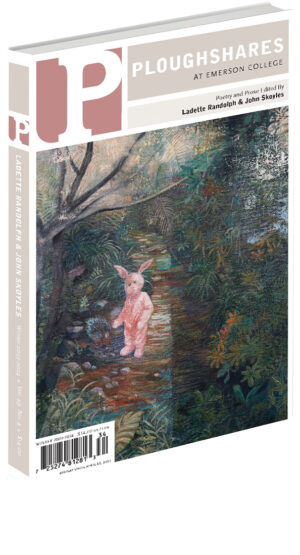

The Winter 2022-23 Issue, edited by Editor-in-chief Ladette Randolph and Poetry Editor John Skoyles, features poetry and prose by Alice Jolly, Natalie Bakopoulos, Carmen Giménez, Grace Li, Sara Elkamel, and more.

The Fall 2022 Issue of Ploughshares features longform work by E. K. Ota, Ben Stroud, Daniel Peña, and others.

The Summer 2022 Issue of Ploughshares, guest-edited by Jamel Brinkley, features original prose by Rav Grewal-Kök, Arinze Ifeakandu, Gothataone Moeng, Lauren Morrow, and others. “As I undertook the pleasurable task of reaching out to writers whose work I love for this issue, I realized I wanted voices that were both skillful and troubling,” Brinkley writes in…

The Spring 2022 Issue, guest-edited by Ilya Kaminsky, features original poetry and prose by Sheila Black, Andres Cerpa, Victoria Chang, Jane Hirshfield, Mary Jo Bang, Paige Lewis, Layli Long Soldier, Khadijah Queen, Hadara Bar-Nadav, Hassaan Mirza, and others.

The Winter 2021-22 Issue, edited by Editor-in-chief Ladette Randolph and Poetry Editor John Skoyles, features poetry and prose by Weike Wang, Fei Sun, Mameve Medwed, Kwame Dawes, and Leila Chatti, among others.

The Fall 2021 Issue. Ploughshares is an award-winning journal of new writing. Since 1971, Ploughshares has discovered and cultivated the freshest voices in contemporary American literature, and now provides readers with thoughtful and entertaining literature in a variety of formats. Find out why the New York Times named Ploughshares “the Triton among minnows.” The Fall 2021 Issue of…

No products in the cart.